Is job growth impressive enough to stop worrying?

A look at unemployment and participation rates

The jobs picture:

unemployment and participation rates

The household report, the

source report for the unemployment rate calculation, registered 428,000 new

jobs in February. It saw 847,000 jobs created in January. That’s nearly 1.3

million jobs in two months. And we still have doubters… And 2.6million jobs have

been created according to the Household report in the last seven months. That’s an average of 371K per month. Private

nonfarm payrolls are up by just 1.3million over that seven month period for an

average of 191K per month. That’s a lot less than the household figure but not

a shabby showing.

Still the labor force

participation rate was around 0.66 (66%) before the recession/financial crisis and

it is only back to 0.639. So 2.1% - more - of the civilian population over the

age of 16 has headed to the side lines helping to suppress the unemployment

rate. Note that this is a proportion and in absolute terms the labor force is

rising; at a 1.6% annual rate over six months.

Population growth shows that

’women’ is the fastest growing class of labor followed by ‘teens’; ‘men’ is the

slowest expanding class.

The labor force shows its

fastest growth for women followed by men with teens the slowest

Employment is fastest growing

for men followed by women and teens. The

number unemployed is shrinking fastest for men second fastest for teens but it

is still rising for women. As a result

of these trends ‘men’ shows the slowest growth among the not in the labor force

groups followed by teens with women having the largest not-in-the-labor-force (NITLF)

growth rate.

Men are making the greatest

gains since they are being employed faster than other groups have the slowest

labor force growth, the fastest reduction in the ranks of unemployed and the

slowest growth of being NITLF. Men’s labor force growth is slow even though

their employment growth (part of the LF measure) is fast.

Cyclical Trends in Participation

The story of labor

force participation rates is being re-written and not just in this cycle. Since

1990 there has been a gradual increase in the tendency for labor force

participation rates to drop. In 1990 it was just the young and adult men along

with all teens. The teen plus adult men’s rate and the adult men’s rate have

steadily been shrinking. But the decline for adult men is accelerating in the

business cycle. So is the decline for teen and adult men. The teen and adult

women rate has been slowing and is now shrinking at an ever faster pace since

1973. Adult women continue to see their participation rate rise, but the pace

of that increase has slowed, and slowed sharply. In an all-inclusive

time-series format the adult women’s rate is down from its peak.

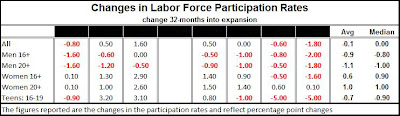

So there are several

kinds of forces that are in play. There are a number of category-specific

longer term trends that are in play. But it is also true that some of these

effects are intensifying over the most recent cycles. Women’s participation rates

once rising by 2.9 % points at the 32 month mark of recovery are up by just

0.10 pct points in this cycle. Historically, that was one of the important offsets

to the long term structural drop in men’s participation rates. The men’s drop

has had some vacillation but it has averaged a drop of 1% at the 32-month mark

of the expansion cycle. In this cycle the men’s rate has dropped by 1.8 %

points. The rate for teens has been dropping in a more accelerated fashion and

the drop of five percentage points at the 32-month mark is identical to the

drop at this point in the 2001 cycle.

In the 1990, 2001,

and 2008 cycles participation rates have been more prone to drop than in earlier

post war cycles. Interestingly 1960 is an exception.

People are

screaming about the high rate of unemployment and the Fed has swerved its policies

to try to reignite growth. Job growth is in gear again but participation rates

channel much broader trends. The Fed needs to be careful about being pushed to

achieve objectives that are beyond its grasp.

The metrics for

participation by educational attainment do not have a long history. But in this

recovery period the rate for those with less than a high school diploma is up

by 0.4% points from the recession end (yes, that’s UP). But for all other

educational; classes it is lower! For

participants with a high school diploma but not college the participation rate

is lower by 3.8% points. For those with some college but no degree the

participation rate is lower by 2.3% points. For those with a college degree

their participation rate is lower by 1.4% points.

The declines in

the unemployment rates have favored the less educated. For the least educated

group (no high school diploma) the drop in the unemployment rate since the

recession ended is 2.6% points; for high school grads it is -1.5% points for

those with some college it is -0.8% and for college grads the drop is 0.6% pts.

Now this also reflects the fact that the level of the unemployment rate is

highest for the least educated. But they still have had the greater

proportionate drop.

Caution Fed caution!!

The table above

breaks down unemployment rate progress by different categories of unemployment:

BY REASON. Job losers probably most come to mind when think of this category.

They make up 55% of it and included workers on temporary layoffs and on permanent

layoff (factories closed, out of business etc). Job leavers made up another 8%,

of the unemployed with re-entrants to the labor force accounting for one

quarter of the unemployed. New entrants are currently about 10% of the pool of

unemployed.

Compared to

historic norms the group ‘not temporarily unemployed’ is quite large. It makes

up 46% of the unemployed pool right now compared with a normal proportion of

37% and a previous high of 40% (1990 and 2001). The proportion unemployed

temporarily is 8.7% compare to an average of 12.1% and a previous low of 10%

(1970).

One implication

here is that a large bulk of the unemployed reflects people that are not simply

going back to their old jobs when the economy picks up.

The Fed may take

its dual mandate seriously. But these data suggest that a great big chuck of

the main unemployment problem is not simply cyclical. ‘Job leavers’ is at a low

proportion historically making up only 7.9% of total unemployment compared to

12% on average at this point in the recovery cycle . But ‘re-entrants’ and ‘new

entrants’ are at a near-normal proportion of total unemployment. Job leavers

may be few in numbers because, with such high unemployment, not many are

willing to leave jobs. So fewer wind up being unemployed. This low reading is

not a mark of success. The low quit rate reinforces this view.

There is another

way to assess unemployment by reason and that is to look at the contribution to

the rate of unemployment. Looked at through this lens the categories for

unemployment are all within one standard deviation of the previous mean for

unemployment by category at this point of the cycle except for ‘not temporary

job losers.’ Of course this means that the overall category that includes

this measure, Job Losers, also is distorted up. But the other component of job

losers, ‘temporary job losers’ is actually normal. What stands out it that the

unemployment rate is elevated by about 1.4 percentage points (it could be 6.9%)

except for the excessive strain on the category ‘not temporary job losers’. The

reading for this category is three standard deviations above the mean., a

reading that makes it impressively significant. And this category is a proper

target for fiscal policy not for monetary policy.

The Fed, as much

as it wants to boost growth, will have to be aware that this large crop of ‘permanent’

unemployed may be harder for the labor market to absorb. Having said that, the

table above show that the current level of permanently unemployed as a

percentage of the recession end peak is only 75% which is the second lowest

among all these cycles. Thus progress in reducing ‘permanent unemployment’ has

been quite good. But this has also been a very large pool of unemployed by

historic standards. Temporary unemployment is at 65% of its peak and that is

about normal at this point of the expansion.

Job leavers are

26% above their peak level but this class averages a higher number; at his stage

the expansion the average rise should be more like 11% not 26%.

Re-entrants are ‘doing

well’ by historic comparison as their ratio to their end recession level is low.

It is up 1% from its recession-end level and the norm would be to rise by 3% to

4%.

New entrants unemployed

are up 39% from their recession-end level while the norm is somewhere between

16% (average) and 25% (median). New

entrants are struggling to get back into the labor market.

On balance a number

of factors are in play in understanding participation rates and unemployment

rates. Many of them are out of the Fed’s control. Some are structural and

others are demographic. The danger is if the Fed pushes too hard to try and get

the unemployment rate down it could backfire. This past week we did see unit

labor costs elevate and they are up for two quarters running and are up to 3%

Yr/Yr. This may not be a sign that the Fed has reached its limits but job growth

is getting stronger has become more reliable with nearly all job gauges giving

off consistently firm readings. Still, the Fed is obsessed with its

multi-mandate. We can only hope that it will recognize, not just that it is

pushing on a string, but that it is pouring stuff into a punch bowl that is already

overflowing.

If might do a

better job of policy recognition error if is not as guilty as I am in mixing its

metaphors.

1 comment:

A low wage job economy.

Post a Comment